Powet Alphabet: S is for 16-bit

by William Talley, filed in Games, Powet Alphabet on May.08, 2010

Since the alphabet is the building block of our language, the Powet Alphabet is the building block of what makes us geeks.

The sixteen bit era of video games is considered by many to be the bridge between the past and modern eras of video gaming, and there were two kings of the ring: Nintendo’s Super Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega’s Genesis. Though there were more powerful systems that sprang up around the time, it would be these two that would outlast and outperform all of them, thanks to their accessibility. This was due not only to the technologies that the two systems boasted under the hood, but also with the library of games that were released for the two. It also gave rise to some of those most heated fanboy wars of our hobby. If you think system wars are bad now, you should have seen how bad it was during the 16-bit days, especially when system manufacturers were openly taking pot shots at each other. However, it was pointless for fanboys of both systems to argue with each other, as both systems not only had an equally impressive library of games (even if many multiplatform releases on the Sega Genesis tended to have inferior audio and visual quality to their SNES counterparts), but they outlasted and outsold the more powerful systems that sprang up around the same period. Click below to take a look back at one of gaming’s most exciting eras.

False Starts: The Intellevision

Technically, the very first 16-bit system was the Intellevision, which went head to head with the Atari 2600. It was a rather unique system, with a controller design that had users inserting overlays for each game. It was the first system to feature in-game voices (via an add-on module), downloadable games (via the PlayCable, a device which allowed users to download games through cable TV, although without a storage device, they were not kept after the system was turned off), and a 16-way direction pad. Though it was superior to Atari’s system, the Intellivision couldn’t hold a candle against the SNES and Genesis. Moreover, it was a pre-video-game crash system, so it wounded up being swept in the dust.

Technically, the very first 16-bit system was the Intellevision, which went head to head with the Atari 2600. It was a rather unique system, with a controller design that had users inserting overlays for each game. It was the first system to feature in-game voices (via an add-on module), downloadable games (via the PlayCable, a device which allowed users to download games through cable TV, although without a storage device, they were not kept after the system was turned off), and a 16-way direction pad. Though it was superior to Atari’s system, the Intellivision couldn’t hold a candle against the SNES and Genesis. Moreover, it was a pre-video-game crash system, so it wounded up being swept in the dust.

Nintendo’s Dominance

Since reviving the video gaming scene back in the 80s with the NES, Nintendo almost single-handedly ruled the gaming landscape, thanks to some heavy handed licensing policies, which affected developers, publishers, and even retailers. First of all, stores were only authorized to carry Nintendo products which carried the Official Nintendo Seal of Quality, a stamp placed on a game by Nintendo to indicate to indicate that it met its standards. Publishers were only allowed to produce 5 games a year, and once they agreed to produce players on Nintendo consoles, they were prohibited from producing them for competitors’ systems. Also, Nintendo retained strict control of the amount of cartridges developers had access to as well as how much advertising their products received in their Nintendo Power magazine. While they were intended to prevent the over-saturation that led to the video game crash, they also severely hampered publishers and developers. More resourceful companies found ways around them. Konami created the Ultra Games sub label to produce more games a year while Color Dreams and Tengen found ways to reverse engineer and work around the lockout chips that Nintendo used to enforce its strict policies. Even so, Nintendo’s rules starved their competitors out of much needed third party support. One of these competitors was the Turbografx-16.

Since reviving the video gaming scene back in the 80s with the NES, Nintendo almost single-handedly ruled the gaming landscape, thanks to some heavy handed licensing policies, which affected developers, publishers, and even retailers. First of all, stores were only authorized to carry Nintendo products which carried the Official Nintendo Seal of Quality, a stamp placed on a game by Nintendo to indicate to indicate that it met its standards. Publishers were only allowed to produce 5 games a year, and once they agreed to produce players on Nintendo consoles, they were prohibited from producing them for competitors’ systems. Also, Nintendo retained strict control of the amount of cartridges developers had access to as well as how much advertising their products received in their Nintendo Power magazine. While they were intended to prevent the over-saturation that led to the video game crash, they also severely hampered publishers and developers. More resourceful companies found ways around them. Konami created the Ultra Games sub label to produce more games a year while Color Dreams and Tengen found ways to reverse engineer and work around the lockout chips that Nintendo used to enforce its strict policies. Even so, Nintendo’s rules starved their competitors out of much needed third party support. One of these competitors was the Turbografx-16.

Close but not Quite: The Turbografx-16

Hudson/NEC’s Turbografx-16, which competed directly against the NES and the Genesis (which had been released around the same time) had a lot of promise, but even though it was billed as a 16-bit system, it was built around an 8-bit microprocessor. It barely outperformed the NES, and even though many of its games had larger sprites, it was unable to do many of the graphical techniques shown on the SNES and Genesis, such as parallax scrolling. It’s high price point, one controller port (requiring players to purchase a multitap if they wished to play with more than one player), and limited marketing didn’t help matters. Even so, the system ended up being more of a success in Japan than in the U.S., particularly when a CD add-on was released from the system (in fact, In Japan, the Mega Drive was actually a distant third behind the Super Fanicom and Turbografx throughout much of the 16-bit era). Another of Nintendo’s competitors wouldn’t go as easily into the darkness…

Hudson/NEC’s Turbografx-16, which competed directly against the NES and the Genesis (which had been released around the same time) had a lot of promise, but even though it was billed as a 16-bit system, it was built around an 8-bit microprocessor. It barely outperformed the NES, and even though many of its games had larger sprites, it was unable to do many of the graphical techniques shown on the SNES and Genesis, such as parallax scrolling. It’s high price point, one controller port (requiring players to purchase a multitap if they wished to play with more than one player), and limited marketing didn’t help matters. Even so, the system ended up being more of a success in Japan than in the U.S., particularly when a CD add-on was released from the system (in fact, In Japan, the Mega Drive was actually a distant third behind the Super Fanicom and Turbografx throughout much of the 16-bit era). Another of Nintendo’s competitors wouldn’t go as easily into the darkness…

The First Runner-Up

There was only one other system that really made an attempt to go against the NES, and had the ability to legitimately do so: The Sega Master System. For the past few decades, Sega had been an innovator in the arcade business, developing games that used primitive 3D technologies years ahead of their time. In 1982, they took their first shot at the game console market and released the SG-1000. It was moderately successful in Japan, and while it was released in South Africa along with select European and Asian countries, it never saw a U.S. release (although Telegames’s Personal Arcade, which WAS released in the U.S. a few years later, could play both SG-1000 and Colecovision games). Unfortunately like many other consoles released during the period, the SG-1000 was swept aside during the video game crash of the mid-80s. Unlike other console developers such as Mattel who either refocused their efforts or gave up completely, Sega didn’t back down. Spurred by the runaway success of the Nintendo Entertainment System, Sega came back with the Sega master System, which was the closest thing to competing with the NES. While Sega’s 8-bit console had a decent following in both the U.S. and Japan, it was Nintendo who dominated 83% of the market share during the 8-bit era. The biggest reason for this was because the Master System couldn’t get the third-party support that had helped the NES remain at the top of the pile. Indeed beside Sega, there were only 2 other third party developers that made Master System games: Activision and Parker Brothers. Still, Sega was determined to remain a player. However, they knew that the next time that they released a system, they would have to do it big. So they went all out.

There was only one other system that really made an attempt to go against the NES, and had the ability to legitimately do so: The Sega Master System. For the past few decades, Sega had been an innovator in the arcade business, developing games that used primitive 3D technologies years ahead of their time. In 1982, they took their first shot at the game console market and released the SG-1000. It was moderately successful in Japan, and while it was released in South Africa along with select European and Asian countries, it never saw a U.S. release (although Telegames’s Personal Arcade, which WAS released in the U.S. a few years later, could play both SG-1000 and Colecovision games). Unfortunately like many other consoles released during the period, the SG-1000 was swept aside during the video game crash of the mid-80s. Unlike other console developers such as Mattel who either refocused their efforts or gave up completely, Sega didn’t back down. Spurred by the runaway success of the Nintendo Entertainment System, Sega came back with the Sega master System, which was the closest thing to competing with the NES. While Sega’s 8-bit console had a decent following in both the U.S. and Japan, it was Nintendo who dominated 83% of the market share during the 8-bit era. The biggest reason for this was because the Master System couldn’t get the third-party support that had helped the NES remain at the top of the pile. Indeed beside Sega, there were only 2 other third party developers that made Master System games: Activision and Parker Brothers. Still, Sega was determined to remain a player. However, they knew that the next time that they released a system, they would have to do it big. So they went all out.

Sega’s Genesis

In 1989, Sega bought their Mega Drive unit over to U.S shores as the Sega Genesis. The Genesis was powered by a 16-architecture similar to the Sega System-16, an arcade board which powered many of Sega’s arcade titles such as Golden Axe and Shinobi. Sega’s Mega-Tech, Mega-Play, and System-C arcade boards are also based upon this tech, so any game developed for the Genesis could be ported to these systems, and vice-versa. Since Nintendo still had third-party developers and publishers on lockdown, Sega had to work to make its system marketable. To that end, Sega hired Michael Katz as CEO of the American branch, and began an aggressive marketing campaign to compete with Nintendo, advertising their system as the place to go to play arcade hits. Perhaps no one game at the time could illustrate this more than the Genesis version of Strider. While the NES version of the game was basically the red-haired lovechild of Metroid and Ninja Gaiden, the Sega Genesis version was the exact same game that players enjoyed in the arcade, complete with all the water cooler moments. Weather you were storming through Eurasia, battling that huge mecha-creature in the jungle, or you were being tossed around by gravity close to the end of the game, it was all here on the Genesis. Other arcade hits followed suit, and the Genesis saw home versions such as E-Swat and Golden Axe that were just like their arcade counterparts. Thanks do a deal with Capcom, Sega was able to develop Genesis versions of games such as Forgotten Worlds and Ghouls n Ghosts. To further establish a look for the Genesis, Sega partnered with various sports figures and celebrities, and produced games bearing their likenesses, such as Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker, Joe Montana Football, and James ‘Buster Douglas’ Boxing. Still, without third party support, Sega’s Genesis still had a hard time establishing itself in North America, so Sega CEO Hayao Nakayama replaced Katz with Tom Kalinske and went back to the drawing board.

In 1989, Sega bought their Mega Drive unit over to U.S shores as the Sega Genesis. The Genesis was powered by a 16-architecture similar to the Sega System-16, an arcade board which powered many of Sega’s arcade titles such as Golden Axe and Shinobi. Sega’s Mega-Tech, Mega-Play, and System-C arcade boards are also based upon this tech, so any game developed for the Genesis could be ported to these systems, and vice-versa. Since Nintendo still had third-party developers and publishers on lockdown, Sega had to work to make its system marketable. To that end, Sega hired Michael Katz as CEO of the American branch, and began an aggressive marketing campaign to compete with Nintendo, advertising their system as the place to go to play arcade hits. Perhaps no one game at the time could illustrate this more than the Genesis version of Strider. While the NES version of the game was basically the red-haired lovechild of Metroid and Ninja Gaiden, the Sega Genesis version was the exact same game that players enjoyed in the arcade, complete with all the water cooler moments. Weather you were storming through Eurasia, battling that huge mecha-creature in the jungle, or you were being tossed around by gravity close to the end of the game, it was all here on the Genesis. Other arcade hits followed suit, and the Genesis saw home versions such as E-Swat and Golden Axe that were just like their arcade counterparts. Thanks do a deal with Capcom, Sega was able to develop Genesis versions of games such as Forgotten Worlds and Ghouls n Ghosts. To further establish a look for the Genesis, Sega partnered with various sports figures and celebrities, and produced games bearing their likenesses, such as Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker, Joe Montana Football, and James ‘Buster Douglas’ Boxing. Still, without third party support, Sega’s Genesis still had a hard time establishing itself in North America, so Sega CEO Hayao Nakayama replaced Katz with Tom Kalinske and went back to the drawing board.

What Nintendon’t

Though Kalinske knew little of the video game business, he surrounded himself with people who did. He began a brand new 4-part marketing plan which in many way was similar to the gamble that Nintendo took when introducing the NES to North America. First of all, the system’s price was cut. Secondly, Kalinske formed a marketing team dedicated to promoting the console to North American audiences, similar to the teams that Nintendo used to first promote the NES. Thirdly, Sega’s advertising became even more aggressive against Nintendo. Who could forget the unforgettable “You can’t do this on Nintendo”, along with it’s spiritual successors the “Sega Scream” and “Welcome to the Next level”? Finally, the pack-in game of Altered Beast was replaced by Sonic the Hedgehog. With Sonic, Sega had a mascot that could compete with Nintendo’s Mario, and the game would be the start of one of gaming’s most prolific franchises. Soon Nintendo would be forced to end their restrictive licensing policies, and in 1990, companies such as Acclaim began to develop games for the Genesis, and soon Sega would would command an increasingly higher market share. Finally, Nintendo had some real competition to face.

Though Kalinske knew little of the video game business, he surrounded himself with people who did. He began a brand new 4-part marketing plan which in many way was similar to the gamble that Nintendo took when introducing the NES to North America. First of all, the system’s price was cut. Secondly, Kalinske formed a marketing team dedicated to promoting the console to North American audiences, similar to the teams that Nintendo used to first promote the NES. Thirdly, Sega’s advertising became even more aggressive against Nintendo. Who could forget the unforgettable “You can’t do this on Nintendo”, along with it’s spiritual successors the “Sega Scream” and “Welcome to the Next level”? Finally, the pack-in game of Altered Beast was replaced by Sonic the Hedgehog. With Sonic, Sega had a mascot that could compete with Nintendo’s Mario, and the game would be the start of one of gaming’s most prolific franchises. Soon Nintendo would be forced to end their restrictive licensing policies, and in 1990, companies such as Acclaim began to develop games for the Genesis, and soon Sega would would command an increasingly higher market share. Finally, Nintendo had some real competition to face.

The War Begins

Sega had released the stylish Genesis to compete with the increasingly aging NES. However, Nintendo wasn’t done yet. Not one to take this lying down, Nintendo released the Super Famicom in the U.S as the Super NES in the late summer of 1991. The SNES was a more technically impressive system than its competitors. It’s advanced graphical capabilities allowed games to easily produce graphical tricks such as advanced tiling, background layer techniques, and mode-7, which gave games a pseudo-3D scaling effect. The 16-bit audio board made for sound effects and music that were more impressive than what was on other systems. Individual game cartridges could even include custom graphics chips, such as the Nintendo’s Super FX (Star Fox, FX Trax) and Capcom’s Cx4 (Mega Man X2) which could further push the system’s capabilities and create new special effects. The dual-grip control pad was also iconic. It contained 4 action buttons on the face, and two trigger buttons on the top. To this day, the basic design remains an influence in later systems, such as the Xbox 360 and the PS1/2/3 controller.

Sega had released the stylish Genesis to compete with the increasingly aging NES. However, Nintendo wasn’t done yet. Not one to take this lying down, Nintendo released the Super Famicom in the U.S as the Super NES in the late summer of 1991. The SNES was a more technically impressive system than its competitors. It’s advanced graphical capabilities allowed games to easily produce graphical tricks such as advanced tiling, background layer techniques, and mode-7, which gave games a pseudo-3D scaling effect. The 16-bit audio board made for sound effects and music that were more impressive than what was on other systems. Individual game cartridges could even include custom graphics chips, such as the Nintendo’s Super FX (Star Fox, FX Trax) and Capcom’s Cx4 (Mega Man X2) which could further push the system’s capabilities and create new special effects. The dual-grip control pad was also iconic. It contained 4 action buttons on the face, and two trigger buttons on the top. To this day, the basic design remains an influence in later systems, such as the Xbox 360 and the PS1/2/3 controller.

However, regaining ground was still an uphill battle. When the SNES launched, there were only a handful of games available compared to the dozens of games available on the TG16 and the Genesis. Not only that, the Genesis’s library was bolstered even more thanks to the Power Base Converter, which allowed Genesis owners to play Master System games on the Genesis, and there was no such device available to allow SNES owners to play their old NES games. Most of the SNES’s early lineup consisted on sequels, remakes, and arcade ports. Many older NES titles received SNES sequels, such as Super Mario World (which added battery backup and huge scaling sprites to Super Mario World 3’s over-world formula), Final Fantasy 2 (which featured an orchestral soundtrack), and Super Castlevania 4 (which also featured an orchestral soundtrack, along with some mode 7 techniques and huge character and enemy sprites). Around this time, developers were exploring the compact disc medium as a gaming format, and the PC market was already well in. The gaming console market would soon follow, although to varying degrees of success.

CD Games: A New Frontier?

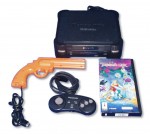

NEC was the first game console manufacturer to release a CD add on in North America. The Turbografx CD released at a very steep $399.99 (which most likely intimated potential customers, especially since the system didn’t have a pack-in game). In 1992, NEC re-upped with the Turboduo. This system combined with the TG16 and the CD and allowed players to play newer ‘Super CD’ discs. Realizing the system’s $299.99 price tag was a bit steep, the game included several pack-in titles such as Bonk’s Adventure and Y’s Book I and II. For the original TG CD, an add-on card was released which allowed players to play Super CD titles without having to buy the new system. Sega, seeing the popularity of the format, released its own Sega CD (or the Mega CD as it was known in Japan) in the U.S 1992 as an add on for the Sega Genesis. Much of the Sega CD’s line up consisted of FMV video game such as Sewer Shark and Night Track. These games, which were basically the illegitimate bastard offspring of the old Space Quest and Dragon’s Lair arcade titles, employed varied production values (sometimes even Hollywood quality, but you wouldn’t know it) and D-list actors and required little interaction on the part of the player. Because of the Sega CD’s limited color palette, the video quality was often muddy and pixelated. Once they were finished, there was little incentive to keep playing. There was an upside to the FMV game genre. PC Adventure games such as Gabriel Knight and Phantasmorgia integrated FMV sequences with the genre’s classic point-and-click gameplay. This paved the way for games such as Final Fantasy 7 and Metal Gear Solid which used cinematics to drive their story along. The other huge majority of the Sega CD’s line up consisted of port-ups of Genesis and arcade titles, usually adding animated sequences and/or a CD soundtrack. That’s not to say that there were no good titles on the Sega CD. In fact the Lunar games became a critically acclaimed role playing game series and was ported to other systems, the Sega CD Sonic game is highly regarded as one of the best in the series, the Sega CD version of Eternal Champions outclassed Mortal Kombat II which had been released that year, and Konami’s Snatcher became a much sought-after cult classic. The Sega CD did better than the TGCD and Duo in North America, although it was a distant third in Japan. Part of the reason for this was the TGCD/Duo’s high price tags and small U.S library (although players could import games from Japan as the system had no region protection). Well, there was also the embarrassingly bad ‘Johnny Turbo’ comic ads, which implied that Sega falsely claimed that it’s CD add-on could play games by itself (Sega never made such a claim, as the Sega CD was always marketed as an add-on). The TGCD flourished more in Japan, where the library included far superior games such as Ys IV and Castlevania: Rondo of Blood. Even so, the high price tag was a deterrent for many buyers, and the CD was discontinued in 1995. Of course Nintendo had also shown an interest in developing a CD add-on for the SNES. First they partnered with Sony, and the deal fell through, eventually resulting in the Playstation. They tried again with Phillips and that deal fell through again, so Nintendo remained with the cartridge format.

NEC was the first game console manufacturer to release a CD add on in North America. The Turbografx CD released at a very steep $399.99 (which most likely intimated potential customers, especially since the system didn’t have a pack-in game). In 1992, NEC re-upped with the Turboduo. This system combined with the TG16 and the CD and allowed players to play newer ‘Super CD’ discs. Realizing the system’s $299.99 price tag was a bit steep, the game included several pack-in titles such as Bonk’s Adventure and Y’s Book I and II. For the original TG CD, an add-on card was released which allowed players to play Super CD titles without having to buy the new system. Sega, seeing the popularity of the format, released its own Sega CD (or the Mega CD as it was known in Japan) in the U.S 1992 as an add on for the Sega Genesis. Much of the Sega CD’s line up consisted of FMV video game such as Sewer Shark and Night Track. These games, which were basically the illegitimate bastard offspring of the old Space Quest and Dragon’s Lair arcade titles, employed varied production values (sometimes even Hollywood quality, but you wouldn’t know it) and D-list actors and required little interaction on the part of the player. Because of the Sega CD’s limited color palette, the video quality was often muddy and pixelated. Once they were finished, there was little incentive to keep playing. There was an upside to the FMV game genre. PC Adventure games such as Gabriel Knight and Phantasmorgia integrated FMV sequences with the genre’s classic point-and-click gameplay. This paved the way for games such as Final Fantasy 7 and Metal Gear Solid which used cinematics to drive their story along. The other huge majority of the Sega CD’s line up consisted of port-ups of Genesis and arcade titles, usually adding animated sequences and/or a CD soundtrack. That’s not to say that there were no good titles on the Sega CD. In fact the Lunar games became a critically acclaimed role playing game series and was ported to other systems, the Sega CD Sonic game is highly regarded as one of the best in the series, the Sega CD version of Eternal Champions outclassed Mortal Kombat II which had been released that year, and Konami’s Snatcher became a much sought-after cult classic. The Sega CD did better than the TGCD and Duo in North America, although it was a distant third in Japan. Part of the reason for this was the TGCD/Duo’s high price tags and small U.S library (although players could import games from Japan as the system had no region protection). Well, there was also the embarrassingly bad ‘Johnny Turbo’ comic ads, which implied that Sega falsely claimed that it’s CD add-on could play games by itself (Sega never made such a claim, as the Sega CD was always marketed as an add-on). The TGCD flourished more in Japan, where the library included far superior games such as Ys IV and Castlevania: Rondo of Blood. Even so, the high price tag was a deterrent for many buyers, and the CD was discontinued in 1995. Of course Nintendo had also shown an interest in developing a CD add-on for the SNES. First they partnered with Sony, and the deal fell through, eventually resulting in the Playstation. They tried again with Phillips and that deal fell through again, so Nintendo remained with the cartridge format.

Of course NEC and Sega weren’t the only companies to invest in CD gaming, and they weren’t the only console developers to compete with Nintendo. Other companies threw their hats into the pile, albeit with mixed, and mostly poor results…

The Competition, or Lack Thereof

Several competitors rose up to compete against the big two, and for a while it was feared that the market would become over-saturated, and there would be another market crash. Thankfully, despite supposedly being more powerful than the SNES and Genesis, these systems tanked for various reasons, most common of which was their high price tags. The best of the worst so to speak, was the 3DO. Designed by Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins, who had envisioned a CD-based platform for developing games that could be licensed out to third parties. Thus in effect, the 3DO was about it’s internal tech rather than the console itself, and models of the 3DO were produced from 4 different manufactures; Panasonic, Sanyo, Goldstar, and Creative Labs (the Creative Labs model was actually a PC card which allowed gamers to play 3DO titles on the PC). Its library consisted of high-res versions of older Sega CD and PC FMV games as well as ports of arcade games such as Super Street Fighter II Turbo and Samurai Showdown (the former was regarded as being superior to the arcade title as it had a CD-quality soundtrack). It also boasted other games such as Gex and Immercenary which were received well. Despite this, the system’s $700 price tag kept it out of many player’s homes. The Phillips CD-I was another critical failure. Not so much of a video game system so much as a glorified disc player, the CD-I’s lineup consisted of game show titles, educational titles, and kids software. Oh yeah, as a by-product of the failed Nintendo-Phillips CD-venture, Phillips had the right to create software featuring various Nintendo characters. The less said about them, the better. It’s controller was ranked the fifth amongst IGN’s worst video game controllers of all time. Despite it’s line up being horrible, the system lasted all the way from 1991 – 1998, and the interactive media techniques employed on the system served as a blueprint of sorts for the DVD format. Then there was the Atari Jaguar. The system that would end up being Atari’s last foray into the console business sported an ugly and horrendously complex controller (#1 on IGN’s worst controller list), a horrific line-up (despite including the excellent Alien vs Predator, Tempest 2000 and ports of Doom and Wolfenstein 3-D), and a CD add-on which made the system look like a miniature toilet seat. Despite being billed as a 64-bit system, the system was barely more powerful than the SNES and Genesis, and the system was discontinued in 1995. On the bright side, when Hasbro bought out the rights to the Atari Corporation and it’s properties, they released the development specs to the Lynx and Jaguar to public domain, opening the door to homebrew development, though I can’t imagine anyone wanting to play the system, much less develop for it. The Pioneer Laseractive, released in 1993 war Pioneer’s attempt at a disc-based gaming console. The unit itself cost $700, and one could purchase add-ons for around $600 each. Surprisingly enough, two of these add-ons were made by Sega and NEC. The Sega add-on allowed users to play Genesis and Sega CD games, while the NEC allowed users to play TG16 and TGCD games. Now keep in mind that at the time of the release, hell, even well before, the Sega Genesis and its CD add-on, the TG-16 and it’s CD add-on, and the TurboDuo were all available for under $600 each. Also, the LaserActive games, nearly all of which required a special module to be played, retailed around $120 each. So you could see why this thing flopped.

Several competitors rose up to compete against the big two, and for a while it was feared that the market would become over-saturated, and there would be another market crash. Thankfully, despite supposedly being more powerful than the SNES and Genesis, these systems tanked for various reasons, most common of which was their high price tags. The best of the worst so to speak, was the 3DO. Designed by Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins, who had envisioned a CD-based platform for developing games that could be licensed out to third parties. Thus in effect, the 3DO was about it’s internal tech rather than the console itself, and models of the 3DO were produced from 4 different manufactures; Panasonic, Sanyo, Goldstar, and Creative Labs (the Creative Labs model was actually a PC card which allowed gamers to play 3DO titles on the PC). Its library consisted of high-res versions of older Sega CD and PC FMV games as well as ports of arcade games such as Super Street Fighter II Turbo and Samurai Showdown (the former was regarded as being superior to the arcade title as it had a CD-quality soundtrack). It also boasted other games such as Gex and Immercenary which were received well. Despite this, the system’s $700 price tag kept it out of many player’s homes. The Phillips CD-I was another critical failure. Not so much of a video game system so much as a glorified disc player, the CD-I’s lineup consisted of game show titles, educational titles, and kids software. Oh yeah, as a by-product of the failed Nintendo-Phillips CD-venture, Phillips had the right to create software featuring various Nintendo characters. The less said about them, the better. It’s controller was ranked the fifth amongst IGN’s worst video game controllers of all time. Despite it’s line up being horrible, the system lasted all the way from 1991 – 1998, and the interactive media techniques employed on the system served as a blueprint of sorts for the DVD format. Then there was the Atari Jaguar. The system that would end up being Atari’s last foray into the console business sported an ugly and horrendously complex controller (#1 on IGN’s worst controller list), a horrific line-up (despite including the excellent Alien vs Predator, Tempest 2000 and ports of Doom and Wolfenstein 3-D), and a CD add-on which made the system look like a miniature toilet seat. Despite being billed as a 64-bit system, the system was barely more powerful than the SNES and Genesis, and the system was discontinued in 1995. On the bright side, when Hasbro bought out the rights to the Atari Corporation and it’s properties, they released the development specs to the Lynx and Jaguar to public domain, opening the door to homebrew development, though I can’t imagine anyone wanting to play the system, much less develop for it. The Pioneer Laseractive, released in 1993 war Pioneer’s attempt at a disc-based gaming console. The unit itself cost $700, and one could purchase add-ons for around $600 each. Surprisingly enough, two of these add-ons were made by Sega and NEC. The Sega add-on allowed users to play Genesis and Sega CD games, while the NEC allowed users to play TG16 and TGCD games. Now keep in mind that at the time of the release, hell, even well before, the Sega Genesis and its CD add-on, the TG-16 and it’s CD add-on, and the TurboDuo were all available for under $600 each. Also, the LaserActive games, nearly all of which required a special module to be played, retailed around $120 each. So you could see why this thing flopped.

There was one other system so to speak, the Neo Geo. Although it tanked as well, it wasn’t because of crappy games or stupid marketing. As a matter of fact, SNK’s system bought arcade titles home by using the exact same boards that the arcade cabinets were ran on. So instead of half-assed ports, versions that had to be developed from the ground up for the system(Genesis Strider), and games that didn’t remotely resemble the arcade game they were based on (NES Strider), we got the actual arcade title. Though it started off with several shooters, platformers, and sports titles, its bread-and-butter became fighting games. Games such as Art of Fighting and Fatal Fury became favorites among collectors. A cd version of the system, released a few years later, tanked due to long load times and low hardware reliability rates. If it wasn’t for the high price tag ($400 – $600 for the unit, $200 for the games), SNK could have been a serious contender to the SNES and Genesis. Of course, this is another story for another time. As their would-be competition floundered around them, Nintendo and Sega chugged right along. However, Sega would soon get a lead on Nintendo. In their quest to provide family-friendly entertainment, Nintendo would create a critical error, and this error would continue to haunt them to this day.

There was one other system so to speak, the Neo Geo. Although it tanked as well, it wasn’t because of crappy games or stupid marketing. As a matter of fact, SNK’s system bought arcade titles home by using the exact same boards that the arcade cabinets were ran on. So instead of half-assed ports, versions that had to be developed from the ground up for the system(Genesis Strider), and games that didn’t remotely resemble the arcade game they were based on (NES Strider), we got the actual arcade title. Though it started off with several shooters, platformers, and sports titles, its bread-and-butter became fighting games. Games such as Art of Fighting and Fatal Fury became favorites among collectors. A cd version of the system, released a few years later, tanked due to long load times and low hardware reliability rates. If it wasn’t for the high price tag ($400 – $600 for the unit, $200 for the games), SNK could have been a serious contender to the SNES and Genesis. Of course, this is another story for another time. As their would-be competition floundered around them, Nintendo and Sega chugged right along. However, Sega would soon get a lead on Nintendo. In their quest to provide family-friendly entertainment, Nintendo would create a critical error, and this error would continue to haunt them to this day.

Moron Kombat

In 1992, Midway’s Mortal Kombat was all the rage, and gamers were eagerly awaiting their chance to play the game at home. MK was a fighting game whose key hook was the massive amount of blood and guts. Punches and kicks drew blood, and at the end of each fight, players could perform fatalities to decapitate their opponent, rip out their still beating heart, and even pull out their spine. With moves this gruesome, parents, teachers, clergymen, and politicians would be outraged. Wanting to avoid the potential negative backlash, Nintendo had Acclaim (who was responsible for developing the home versions) remove the violent fatalities and replace them with non-gory (and glitch-like) ‘finishing moves’. The Sega versions on the other hand, had the blood accessible via a code. Even though the SNES version’s graphics and sound was closer to the arcade game, it didn’t matter, since the SNES version didn’t have the blood. So while Nintendo may have successfully avoided the media backlash, the backlash from gamers had just begun. To this day, Nintendo consoles would be tagged (many times unfairly) as kid’s toys. Sega on the other hand, saw it’s popularity soar upwards as the Genesis was now regarded as the ‘cooler’ system. In fact, at the time, many teens would not admit to owning an SNES over a Genesis, as revealed by a Sony-conducted focus group. With titles such as Streets of Rage, Vectorman, Sonic 2, and Castlevania Bloodlines, Sega’s library expanded, offering players a selection of soon-to-be classic games that pushed the hardware to its limits in order to compete with the best of what Nintendo had to offer. They even attempted to make a foray into the 32 bit market with the forthcoming Saturn and the Sega 32X add on. However, in doing so, they made a few critical mistakes of their own.

In 1992, Midway’s Mortal Kombat was all the rage, and gamers were eagerly awaiting their chance to play the game at home. MK was a fighting game whose key hook was the massive amount of blood and guts. Punches and kicks drew blood, and at the end of each fight, players could perform fatalities to decapitate their opponent, rip out their still beating heart, and even pull out their spine. With moves this gruesome, parents, teachers, clergymen, and politicians would be outraged. Wanting to avoid the potential negative backlash, Nintendo had Acclaim (who was responsible for developing the home versions) remove the violent fatalities and replace them with non-gory (and glitch-like) ‘finishing moves’. The Sega versions on the other hand, had the blood accessible via a code. Even though the SNES version’s graphics and sound was closer to the arcade game, it didn’t matter, since the SNES version didn’t have the blood. So while Nintendo may have successfully avoided the media backlash, the backlash from gamers had just begun. To this day, Nintendo consoles would be tagged (many times unfairly) as kid’s toys. Sega on the other hand, saw it’s popularity soar upwards as the Genesis was now regarded as the ‘cooler’ system. In fact, at the time, many teens would not admit to owning an SNES over a Genesis, as revealed by a Sony-conducted focus group. With titles such as Streets of Rage, Vectorman, Sonic 2, and Castlevania Bloodlines, Sega’s library expanded, offering players a selection of soon-to-be classic games that pushed the hardware to its limits in order to compete with the best of what Nintendo had to offer. They even attempted to make a foray into the 32 bit market with the forthcoming Saturn and the Sega 32X add on. However, in doing so, they made a few critical mistakes of their own.

Sega Competes with Itself

Where as Nintendo tried to hard to make kid friendly products., Sega spread themselves thin with products that were either superfluous or just weren’t that good. The 32X was a prime example. The cartridge-based add-on for the Genesis boasted a color palette of 32,760 colors, although most games released on the unit only looked slightly better than most Genesis and SNES titles released at the time. There were even games that required the Sega CD to be attached to the unit, one of which being an enhanced version of Night Trap. As all three had their own AC adapters, this made things very problematic for one’s power bill. Recognizing the problems with the 32X, Sega planned another console, the Neptune, which would combine both the 32X and the Genesis into one unit. However, this would eventually be scrapped as the Saturn was preparing it’s North American debut by the time a prototype had become available. Overall, it didn’t make much sense for Sega to have a 32 bit add-on in the market when they were preparing to release a legitimate 32-bit gaming system, especially when said add-on couldn’t produce the 3-D polygon techniques that were done by the Nintendo 64 and the Playstation. It wasn’t exactly flying off store shelves either, as it was selling as low as $19.99 by the end of it’s life-cycle.

Where as Nintendo tried to hard to make kid friendly products., Sega spread themselves thin with products that were either superfluous or just weren’t that good. The 32X was a prime example. The cartridge-based add-on for the Genesis boasted a color palette of 32,760 colors, although most games released on the unit only looked slightly better than most Genesis and SNES titles released at the time. There were even games that required the Sega CD to be attached to the unit, one of which being an enhanced version of Night Trap. As all three had their own AC adapters, this made things very problematic for one’s power bill. Recognizing the problems with the 32X, Sega planned another console, the Neptune, which would combine both the 32X and the Genesis into one unit. However, this would eventually be scrapped as the Saturn was preparing it’s North American debut by the time a prototype had become available. Overall, it didn’t make much sense for Sega to have a 32 bit add-on in the market when they were preparing to release a legitimate 32-bit gaming system, especially when said add-on couldn’t produce the 3-D polygon techniques that were done by the Nintendo 64 and the Playstation. It wasn’t exactly flying off store shelves either, as it was selling as low as $19.99 by the end of it’s life-cycle.

The 32X wasn’t Sega’s only flop either. In 1994, Sega had released the Pico, which was a system designed to get younger players to play video games (getting small children to sit in front of their video game screen instead of going outside and being active, one can only imagine how well this could have gone over with parents). It was discontinued in North America and Europe around 1996 and 1997. As far as educational software goes, it wasn’t horrible, and the Pico was more of a causality of Sega’s decision to focus on the Saturn rather than any issues with the product itself. In Japan, new games were produced for the unit as recently as 2003, when a game based on Nintendo’s Pokemon hit the console. That’s right, a Nintendo product on a Sega system. By the end of 1995, Sega, along with many third parties that developed games for their systems, were either actively supporting and/or providing software for 8 different formats: The Master System, Genesis, Game Gear, Sega CD, 32X, 32X CD, Saturn, and Pico.

The 32X wasn’t Sega’s only flop either. In 1994, Sega had released the Pico, which was a system designed to get younger players to play video games (getting small children to sit in front of their video game screen instead of going outside and being active, one can only imagine how well this could have gone over with parents). It was discontinued in North America and Europe around 1996 and 1997. As far as educational software goes, it wasn’t horrible, and the Pico was more of a causality of Sega’s decision to focus on the Saturn rather than any issues with the product itself. In Japan, new games were produced for the unit as recently as 2003, when a game based on Nintendo’s Pokemon hit the console. That’s right, a Nintendo product on a Sega system. By the end of 1995, Sega, along with many third parties that developed games for their systems, were either actively supporting and/or providing software for 8 different formats: The Master System, Genesis, Game Gear, Sega CD, 32X, 32X CD, Saturn, and Pico.

Nintendo’s Third Renaissance

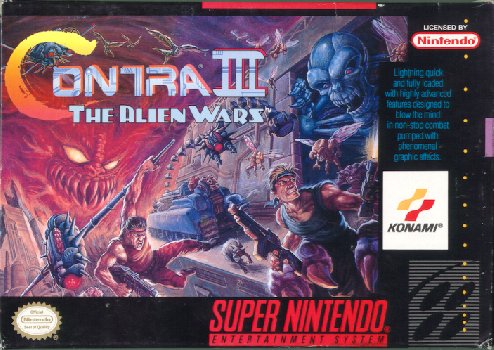

Nintendo on the other hand, only had to worry about the SNES and Game Boy for the majority of the mid 90s period, and thus they weren’t as overstretched. In addition to that, Nintendo had just started development on it’s Ultra 64 platform, the system that would then go on to become the Nintendo 64. It had partnered with a slew of developers and publishers who were committed to producing software for the platform. Among this ‘Dream Team’ were DMA designs, Rare, and Midway. Having learned their lesson from the Mortal Kombat fiasco, and with the establishment of a new ESRB ratings system on the horizon, Nintendo allowed Acclaim to leave the blood and guts intact for the SNES release of Mortal Kombat II. Thus, the SNES release of the game was the closest players could get to the arcade. Well, at least it was without having to buy a pseudo-32-bit add-on, and since the 32X, which was released months later, didn’t exactly move a massive amount of units, the SNES remained the preferred platform for the game. Therefore, Nintendo began to regain some of the fans they lost over the past few years. The period between 1994 – 1996 saw some of the console’s best and most innovated titles as well. Square bought over the classic RPGs Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy 6 (or 3 as it was known over here), Nintendo released Yoshi’s Island, which had cartoon-like graphics and was powered by the Super Fx chip (although you wouldn’t tell, as most games utilizing the device had 3-D Polygonial looks), and then there was Donkey Kong Country. Developed by N64 dream team member Rare, DKC made use of 3-D computer graphics rendering which was unheard of at the time of its release, and the game’s graphics (on a 16-bit system) rivaled those of many games available on ‘next-generation’ systems. At the heart of the game, it was the same hop-n-bop platforming gameplay that had been around since the days of Mario, but it didn’t matter since it was so awesome to look at, and it gave a sign of things to come. Now things weren’t all rosy for Nintendo however. 1995 saw the U.S release of the disastrous Virtual Boy. The handheld, whose screens were in red and black was Nintendo’s entry into the 32 bit market. More accurately, it was meant to tide players over until the Nintendo 64 was released. However, the thing sold so poorly that it was discontinued the following year. Eventually, the end was nearing for both the SNES and Genesis, as one next-gen competitor was quickly gaining leeway into the video game console market.

Nintendo on the other hand, only had to worry about the SNES and Game Boy for the majority of the mid 90s period, and thus they weren’t as overstretched. In addition to that, Nintendo had just started development on it’s Ultra 64 platform, the system that would then go on to become the Nintendo 64. It had partnered with a slew of developers and publishers who were committed to producing software for the platform. Among this ‘Dream Team’ were DMA designs, Rare, and Midway. Having learned their lesson from the Mortal Kombat fiasco, and with the establishment of a new ESRB ratings system on the horizon, Nintendo allowed Acclaim to leave the blood and guts intact for the SNES release of Mortal Kombat II. Thus, the SNES release of the game was the closest players could get to the arcade. Well, at least it was without having to buy a pseudo-32-bit add-on, and since the 32X, which was released months later, didn’t exactly move a massive amount of units, the SNES remained the preferred platform for the game. Therefore, Nintendo began to regain some of the fans they lost over the past few years. The period between 1994 – 1996 saw some of the console’s best and most innovated titles as well. Square bought over the classic RPGs Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy 6 (or 3 as it was known over here), Nintendo released Yoshi’s Island, which had cartoon-like graphics and was powered by the Super Fx chip (although you wouldn’t tell, as most games utilizing the device had 3-D Polygonial looks), and then there was Donkey Kong Country. Developed by N64 dream team member Rare, DKC made use of 3-D computer graphics rendering which was unheard of at the time of its release, and the game’s graphics (on a 16-bit system) rivaled those of many games available on ‘next-generation’ systems. At the heart of the game, it was the same hop-n-bop platforming gameplay that had been around since the days of Mario, but it didn’t matter since it was so awesome to look at, and it gave a sign of things to come. Now things weren’t all rosy for Nintendo however. 1995 saw the U.S release of the disastrous Virtual Boy. The handheld, whose screens were in red and black was Nintendo’s entry into the 32 bit market. More accurately, it was meant to tide players over until the Nintendo 64 was released. However, the thing sold so poorly that it was discontinued the following year. Eventually, the end was nearing for both the SNES and Genesis, as one next-gen competitor was quickly gaining leeway into the video game console market.

The Rise of Sony and the Twilight of the 16-bit Years

Sony had been a third party developer for both Nintendo and Sega. When their deal with Nintendo to create a CD-based system fell through, it was strongly hinted that the technology was used in the forthcoming Playstation unit. The PS1 was released in late 1995, and along with the Saturn, was regarded as one of the first consoles to do disc-based gaming right. Sony marketed its product towards the older generation who had grown up with Nintendo and Sega products, and the console was depicted alongside the TV and VCR as being a necessary part of one’s entertainment center. Throughout the next several years, Sony would assume dominance over it’s competitors, although this is another story for another time. You can read most of this story in our Playstation One article.

Sony had been a third party developer for both Nintendo and Sega. When their deal with Nintendo to create a CD-based system fell through, it was strongly hinted that the technology was used in the forthcoming Playstation unit. The PS1 was released in late 1995, and along with the Saturn, was regarded as one of the first consoles to do disc-based gaming right. Sony marketed its product towards the older generation who had grown up with Nintendo and Sega products, and the console was depicted alongside the TV and VCR as being a necessary part of one’s entertainment center. Throughout the next several years, Sony would assume dominance over it’s competitors, although this is another story for another time. You can read most of this story in our Playstation One article.

Sega of Japan’s CEO decided to discontinue all Sega systems beside the Saturn. This hurt the Genesis in North America, where unlike in Japan (where it was a distant third behind NEC), it was still closely following after Nintendo, and there was still a strong user-base for the system. Not only that, third parties were having a difficult time developing for the Saturn, and soon it would be discontinued in favor of the Dreamcast. The next few years saw the prerequisite third party multiplatform ports, the disappointing Sonic 3D blast, and a god-awful Genesis port of Virtua Fighter 2. The last official Sega Genesis (and SNES) release of the era was Frogger, which was released in 1998. Nintendo on the other hand, despite having just released the Nintendo 64 (which was also hard for third party development) continued to support the SNES for as long as it could, and a few third-party developers continued to do so as well. Capcom in particular had originally intended to pull the plug on several SNES games it had in development, including Mega Man 7, Marvel Super Heroes, and Breath of Fire 2 when fans began a massive letter writing campaign, leaving the publisher no choice to put them back on the release schedule. Along with Final Fight 3 and Mega Man X3, they became the original Capcom 5 (my name, not the medias). Of course this became the Capcom 6 when Nintendo published a SNES port of Street Fighter Alpha 2 in the fall of 1996. Square-soft partnered with Nintendo to produce the critically acclaimed Super Mario RPG, and Natsume showed more RPG love with Lufia 2. The last first-party game for the system was Kirby Dream land 3, which was released in 1997 (it’s a shame that Nintendo couldn’t have held out for another year or so, otherwise Nintendo gamers could have seen a North American release of the awesome Mega Man and Bass), and production of the console ceased in 1999. In Japan, support for the system continued all the way until late 2000, and the system’s production ceased in 2003. The last game released for it was Metal Slader Glory Director’s Cut, a graphic novel style game. Like that, the 16-bit era of gaming went out not with a bang, but a trickle and fade.

Or did it? (Epilogue)

As the law of conservation of mass dictates, nothing is truly gone forever, and this was true with 16-bit gaming. Although the SNES, Genesis, and Turbografx-16 have been discontinued officially for over a decade and third parties have stopped officially supporting the consoles, the 16-bit gaming scene has been alive as ever, thanks in no small part to the illegal emulation/ROM scene. Rom hackers have provided translations for many Japan-only release such as Final Fantasy 5, and have opened the doors for homebrew development. There were legal ways of keeping the systems alive too. The Game Boy Advance’s library contains several upgrades/re-releases of classic SNES and Genesis titles such as A Link to the Past, Super Ghouls and Ghosts, and Breath of Fire. In many cases, new features have been added to each game. Also, many GBA and DS titles have been created within the spirit of the era, with graphics and gameplay mechanics that are reminiscent of the 16-bit days of gaming. Titles such as Contra 4 and mega Man ZX may be more recent, but they give gamers an excellent throwback to yesteryear. If course the Wii’s Virtual Console service contains many classic releases, not only for NES, N64, and SNES, but for Genesis, Master System, and TG-16, despite all of them being competitors less than a decade ago!

As the law of conservation of mass dictates, nothing is truly gone forever, and this was true with 16-bit gaming. Although the SNES, Genesis, and Turbografx-16 have been discontinued officially for over a decade and third parties have stopped officially supporting the consoles, the 16-bit gaming scene has been alive as ever, thanks in no small part to the illegal emulation/ROM scene. Rom hackers have provided translations for many Japan-only release such as Final Fantasy 5, and have opened the doors for homebrew development. There were legal ways of keeping the systems alive too. The Game Boy Advance’s library contains several upgrades/re-releases of classic SNES and Genesis titles such as A Link to the Past, Super Ghouls and Ghosts, and Breath of Fire. In many cases, new features have been added to each game. Also, many GBA and DS titles have been created within the spirit of the era, with graphics and gameplay mechanics that are reminiscent of the 16-bit days of gaming. Titles such as Contra 4 and mega Man ZX may be more recent, but they give gamers an excellent throwback to yesteryear. If course the Wii’s Virtual Console service contains many classic releases, not only for NES, N64, and SNES, but for Genesis, Master System, and TG-16, despite all of them being competitors less than a decade ago!

Sega on the other hand, has had the biggest posthumous following. With Sega no longer a console manufacturer, the company has released many of its classic titles by way of the many compilation discs that they have released over the years. The console itself is still around to speak, as it’s possibly received the most hardware revisions out of any console, be it an officially licensed product, an international release, or even a bootleg. Many of these new versions either omitted features with the aims of cutting costs (most of them didn’t support any of the add-ons) and many of them were region-free, meaning they could play most internationally released games. In 1997, Sega licensed the Genesis hardware to Majesco, who released it at a budget price before developing a third version of the console. There have even been new commercial releases for the system. In 2006, Super Fighter Team released Beggar Prince, which was translated from a 1996 Chinese Genesis title. They followed it up in 2008 with The Legend of Wukong, also translated from a Chinese original. A team of homebrew developers are hard at work on the RPG Pier Solar and the Great Architects, which is being developed from the ground up for the Genesis.

Sega on the other hand, has had the biggest posthumous following. With Sega no longer a console manufacturer, the company has released many of its classic titles by way of the many compilation discs that they have released over the years. The console itself is still around to speak, as it’s possibly received the most hardware revisions out of any console, be it an officially licensed product, an international release, or even a bootleg. Many of these new versions either omitted features with the aims of cutting costs (most of them didn’t support any of the add-ons) and many of them were region-free, meaning they could play most internationally released games. In 1997, Sega licensed the Genesis hardware to Majesco, who released it at a budget price before developing a third version of the console. There have even been new commercial releases for the system. In 2006, Super Fighter Team released Beggar Prince, which was translated from a 1996 Chinese Genesis title. They followed it up in 2008 with The Legend of Wukong, also translated from a Chinese original. A team of homebrew developers are hard at work on the RPG Pier Solar and the Great Architects, which is being developed from the ground up for the Genesis.

More than anything, the SNES and Genesis will be remembered as demonstrating that it’s not about the hardware that you are working with, but what you do with it. When you have games such as Donkey Kong Country and Vectorman outlasting the supposedly more powerful 3DO, then you know you got something special. Many of the lessons learned during these years would grow to shape gaming for years to follow. Sadly, not too many companies have this king of work ethic anymore, not even Nintendo and Sega.

PS3

PS3

Famicom Dojo

Famicom Dojo KEEP PLAYING

KEEP PLAYING KEEP PLAYING: Rewind

KEEP PLAYING: Rewind Powet Toys

Powet Toys Powetcast

Powetcast Hitchhiker's Guide POWETcast

Hitchhiker's Guide POWETcast