The Powet Top 5 – Reasons Nintendo Can’t/Won’t/Shouldn’t Go Third Party

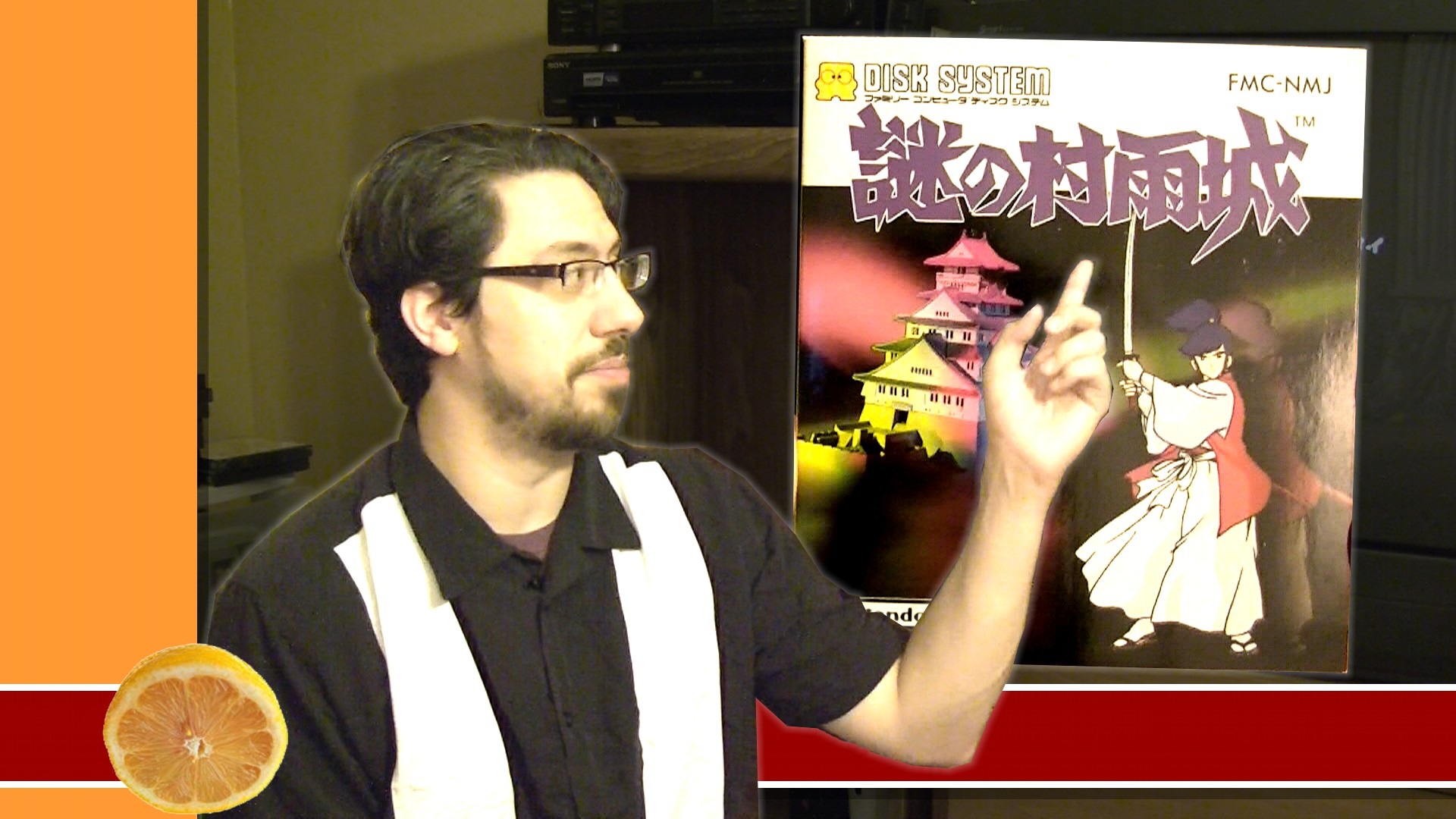

by Sean "TheOrange" Corse, filed in Articles, Powet Top 5 on Feb.09, 2012

When Nintendo reported two straight quarterly losses in early 2011, followed by a less-than-stellar initial release of its new 3DS handheld console, it didn’t take long for the naysayers to begin spelling the company’s doom.

This is a familiar dance. It started in the ’90s, when Nintendo’s veneer of dominance started cracking in the face of competition with the Sega Genesis. Or maybe it was the decision to abandon the CD format for the Nintendo 64 when Sega and Sony made the leap. Or perhaps it was because, even with the GameCube, no Nintendo console had sold better than its predecessor — that is, until the release of the Wii.

However, despite calls that Nintendo abandon its hardware ambitions — even with the new wrinkle of the ever-rising iOS platform — there are plenty of reasons why Nintendo would never, could never, and should never stop making TV or handheld consoles.

Here are the top five:

Welcome, Poweteers, to a brand new original column where we explore the top (and bottom) 5 items we think are relevant to any of a variety of topics that span the imagination. Sit back, read, and respond!

5) Nintendo is really a platform company, not a game company

Yes, obviously, they make games. But they make games for their own consoles, and no other. This supposed reticence to make their games available on other platforms is the crux of the argument against their current model; there are plenty of people who buy and play Nintendo games, and apparently many more who would play them but for the fact that they must own a Nintendo system to do it.

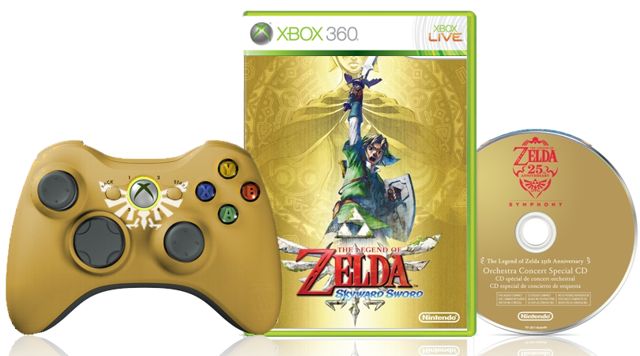

To be sure, there are reasons some avoid doing so: the Wii is graphically under-powered compared to its competitors in the Sony Playstation 3 and Microsoft’s Xbox 360. The online service is noticeably poorer and far more obtuse, which is something that its fans (even this one) can readily admit. Even with its innovative Wii remote, many of Nintendo’s first-party games play better with the backwards compatible GameCube or Wavebird controllers, where the option exists.

To be sure, there are reasons some avoid doing so: the Wii is graphically under-powered compared to its competitors in the Sony Playstation 3 and Microsoft’s Xbox 360. The online service is noticeably poorer and far more obtuse, which is something that its fans (even this one) can readily admit. Even with its innovative Wii remote, many of Nintendo’s first-party games play better with the backwards compatible GameCube or Wavebird controllers, where the option exists.

But even if Nintendo doesn’t completely abandon the console market, why not at least start releasing games for other platforms? Aren’t they just leaving money on the table?

I thought that might be the case until I read this article by Google employee Steve Yegge ranting about the poor approach of Google+, and praising the tactics and vision of Apple, Facebook and his previous employer Amazon. After that, it became clear what Nintendo’s overall business philosophy is really about, and why they would be unlikely to abandon it in whole or in part because of a few “ouchies” in 2011.

Despite the up-and-coming status of iOS gaming, the Nintendo DS still holds the title of the best selling handheld console in the world, and just a hair shy of the best selling game machine of any kind.

Nintendo doesn’t just make world-class hardware, but they also make some of the most popular games with the most iconic characters in the world; in the 1990s, Mario was more recognizable than Mickey Mouse. Like any good platform company, however, the strength and drive to create their games has everything to do with selling their hardware, and convincing other developers to create their games for that hardware as well. Their games act as proof of concept applications for what their hardware innovations can do, and Nintendo certainly does love to innovate.

Nintendo doesn’t just make world-class hardware, but they also make some of the most popular games with the most iconic characters in the world; in the 1990s, Mario was more recognizable than Mickey Mouse. Like any good platform company, however, the strength and drive to create their games has everything to do with selling their hardware, and convincing other developers to create their games for that hardware as well. Their games act as proof of concept applications for what their hardware innovations can do, and Nintendo certainly does love to innovate.

4) Nintendo has a robust and legendary R&D department, the members of which would all lose their jobs if they stopped making hardware

Granted, many of the company’s most famous designers are retired or (sadly) deceased, but you know their works even if you don’t know their names.

The most prolific of these designers — in both hardware and software — is Gunpei Yokoi, Nintendo’s handheld gaming savant. He created the photosensitive hardware of the light gun first seen in Wild Gunman arcade cabinets and later the NES Zapper. Even if you don’t remember the Game & Watch series, you certainly remember the directional pad, which was an innovation necessary to achieve 8-way control on a device that was not friendly to traditional Atari’s arcade-like game paddles. He designed R.O.B the Robot, the Game Boy, and the ill-fated Virtual Boy.

The most prolific of these designers — in both hardware and software — is Gunpei Yokoi, Nintendo’s handheld gaming savant. He created the photosensitive hardware of the light gun first seen in Wild Gunman arcade cabinets and later the NES Zapper. Even if you don’t remember the Game & Watch series, you certainly remember the directional pad, which was an innovation necessary to achieve 8-way control on a device that was not friendly to traditional Atari’s arcade-like game paddles. He designed R.O.B the Robot, the Game Boy, and the ill-fated Virtual Boy.

In addition to the directional pad, Nintendo gave the world cartridge saves, shoulder buttons, the analog stick, force feedback, “waggle”, and most recently glasses-less 3D. In fact, the directional pad (as one of their first major innovations) has such staying power that Nintendo wasn’t able to find a way to replace it in favor of other inputs, despite trying to do so in early designs of both the GameCube and Wii controllers.

In addition to the directional pad, Nintendo gave the world cartridge saves, shoulder buttons, the analog stick, force feedback, “waggle”, and most recently glasses-less 3D. In fact, the directional pad (as one of their first major innovations) has such staying power that Nintendo wasn’t able to find a way to replace it in favor of other inputs, despite trying to do so in early designs of both the GameCube and Wii controllers.

After the release of the GameCube, believable arguments could have been made (and often were) that Nintendo had precious little left to offer the video game market aside from its games. Time has since shown that was not the case — analog sticks and built-in rumble are now standard features of all modern consoles — but all the same this was the time when the calls for Nintendo to stop making hardware were the loudest.

Had they done so, they would have been no Wii, and possibly no Playstation Move or Kinect as a result. Nintendo didn’t develop glasses-less 3D technology, but what other company would have given that technology a chance on one of its consoles, especially after the initial ridicule they suffered for announcing such a feature?

Had they done so, they would have been no Wii, and possibly no Playstation Move or Kinect as a result. Nintendo didn’t develop glasses-less 3D technology, but what other company would have given that technology a chance on one of its consoles, especially after the initial ridicule they suffered for announcing such a feature?

At Nintendo, games have always come second to these hardware features. Would their software designers (who, like Yokoi, were also sometimes the hardware designers) be able to thrive as a third-party company where they could not influence the consoles and other devices for which they released their games? It would be an environment that is totally alien to their culture, and would decimate Nintendo as a business.

3) Nintendo has been more on top than not

The myth of Nintendo’s irrelevance as a hardware maker largely just that.

In the 1980s, Nintendo was the undisputed king of the home console gaming. It’s no oversized claim that the Nintendo Entertainment System revived the video game market in the United States when it was released in 1985. But Nintendo was already on top of the Japanese market with the release of the original Family Computer (a.k.a. “Famicom”) in 1983, far outstripping fellow Japanese rival Sega with its series of SG-1000 home video game consoles that eventually lead to the US-released 8-bit Sega Master System.

In the 1980s, Nintendo was the undisputed king of the home console gaming. It’s no oversized claim that the Nintendo Entertainment System revived the video game market in the United States when it was released in 1985. But Nintendo was already on top of the Japanese market with the release of the original Family Computer (a.k.a. “Famicom”) in 1983, far outstripping fellow Japanese rival Sega with its series of SG-1000 home video game consoles that eventually lead to the US-released 8-bit Sega Master System.

When Sega Genesis started giving Nintendo a run for its money in the ’90s, it was only a danger in the US market. In Japan, the “Mega Drive” was only ever a third-rate console. Who was second? NEC’s PC Engine, otherwise known at the TurboGrafx-16 in North America. It wasn’t until Sony’s entry into the video game market a few years later that Nintendo’s top spot was decisively stripped away on both sides of the Pacific.

Even while the home console wars were raging, Nintendo was the undisputed champion (and, fairly, the progenitor) of the handheld video game market — first with the Game Boy, and all the way through the Nintendo DS to the end of the last decade. The Sega Game Gear, the Neo Geo Pocket, Bandai’s WonderSwan, and even Sony’s Playstation Portable all failed to knock Nintendo from its perch.

Even while the home console wars were raging, Nintendo was the undisputed champion (and, fairly, the progenitor) of the handheld video game market — first with the Game Boy, and all the way through the Nintendo DS to the end of the last decade. The Sega Game Gear, the Neo Geo Pocket, Bandai’s WonderSwan, and even Sony’s Playstation Portable all failed to knock Nintendo from its perch.

A poor showing in 2011 didn’t oust the Wii as the #1 modern day console, and didn’t make much of a dent in Nintendo’s more-than-ample reserves. What they lost was at least somewhat made up with improved sales of the 3DS that ultimately beat out the first year of Nintendo DS sales by the end of 2011.

Nintendo’s success in both these markets over the last six years was driven largely by casting a wider net in what seemed to be a shrinking ecosystem.

2) Going software-only didn’t work out so well for (most of) Nintendo’s competitors

Let’s talk crazy for a moment and say that the previous three reasons were not good enough to discourage anyone — including Nintendo — from ditching their hardware business in favor of going software-only. Let’s say they have a strategy for doing software on other platforms, and they’re going to go with it.

Trouble is, they’re probably going to fail.

“But what about Sega?” you ask. Sega is indeed the go-to answer when one asks why on Earth Nintendo would want to stop making hardware. But let’s talk about some other hardware makers first.

Atari was the king of the US market before the video game crash — something that they had no small part in causing. Their last-ditch console effort came out at the same time as the N64 in the form of the Jaguar. Even a CD attachment couldn’t help it compete with the far more dominant Playstation 2, or catapault it above the floundering cartridge only (at least in America) N64. Atari tried to refashion itself in the 21st century as a video game publisher, but can you name the last Atari game you played?

Atari was the king of the US market before the video game crash — something that they had no small part in causing. Their last-ditch console effort came out at the same time as the N64 in the form of the Jaguar. Even a CD attachment couldn’t help it compete with the far more dominant Playstation 2, or catapault it above the floundering cartridge only (at least in America) N64. Atari tried to refashion itself in the 21st century as a video game publisher, but can you name the last Atari game you played?

HudsonSoft’s only contribution to the home console market as a hardware maker was with the TurboGrafx-16 and PC Engine, along with co-creators NEC. (They were also partly responsible for the PC-FX, but you probably don’t know about that and possibly don’t care.) Hudson went public in 2001, and by 2002 were majority-controlled by mega-publisher Konami. The company hardly went away after that, but apart from the odd Bomberman game you probably didn’t play any of their titles. That is, unless you played Mario Party 1-8. Just this year, Hudson announced it would be closing its doors.

HudsonSoft’s only contribution to the home console market as a hardware maker was with the TurboGrafx-16 and PC Engine, along with co-creators NEC. (They were also partly responsible for the PC-FX, but you probably don’t know about that and possibly don’t care.) Hudson went public in 2001, and by 2002 were majority-controlled by mega-publisher Konami. The company hardly went away after that, but apart from the odd Bomberman game you probably didn’t play any of their titles. That is, unless you played Mario Party 1-8. Just this year, Hudson announced it would be closing its doors.

If not for the entry of Sony and then Microsoft into the home console market, Nintendo would have no competitors left. Except for Sega.

Sega’s well-known last console was the Dreamcast. The hardware was being sold at a loss, with the hopes that the difference would be made up with first party titles and third party licensing. The Dreamcast was a fine machine, but ultimately those hardware losses could not be recouped when third parties jump ship in favor of Sony’s new Playstation 2.

Sega’s well-known last console was the Dreamcast. The hardware was being sold at a loss, with the hopes that the difference would be made up with first party titles and third party licensing. The Dreamcast was a fine machine, but ultimately those hardware losses could not be recouped when third parties jump ship in favor of Sony’s new Playstation 2.

Nintendo’s situation with the N64 and GameCube was wholly different. A common complaint (that at least this author heard) was how little interest Nintendo seemed to have in courting third parties, that they didn’t need them. The defection of RPG makers Enix and Square to Sony’s platform could have been as fatal of a blow for Nintendo as was the flight of third parties from the Dreamcast was for Sega. The major difference is that Nintendo was not selling its hardware at a loss, and so did not require expansive third party support as part of their profit strategy.

Nintendo’s situation with the N64 and GameCube was wholly different. A common complaint (that at least this author heard) was how little interest Nintendo seemed to have in courting third parties, that they didn’t need them. The defection of RPG makers Enix and Square to Sony’s platform could have been as fatal of a blow for Nintendo as was the flight of third parties from the Dreamcast was for Sega. The major difference is that Nintendo was not selling its hardware at a loss, and so did not require expansive third party support as part of their profit strategy.

Nintendo also had its robust handheld market to fall back on with the Game Boy and then the DS. (Readers with a long memory might remember the introduction of the DS as a “third pillar” to complement the Game Boy Advance and GameCube.) Third parties had no problem releasing successful titles for these platforms, and Nintendo profited handsomely from the arrangement.

Sega’s Game Gear and Nomad never saw that kind of success. The company was already wounded financially by the performance of the Saturn in the previous generation. Between 1984 and 1988, Sega released four variations of its SG-1000 hardware in Japan (leading to two variations of the Sega Master System), while at the same time Nintendo only had the Famicom and its American counterpart the NES. Even with its successful Genesis console, Sega sank money into the more poorly-selling Sega CD and 32x attachments.

Sega’s Game Gear and Nomad never saw that kind of success. The company was already wounded financially by the performance of the Saturn in the previous generation. Between 1984 and 1988, Sega released four variations of its SG-1000 hardware in Japan (leading to two variations of the Sega Master System), while at the same time Nintendo only had the Famicom and its American counterpart the NES. Even with its successful Genesis console, Sega sank money into the more poorly-selling Sega CD and 32x attachments.

Sega was hemorraghing so much cash when the Dreamcast went under, the only way it could survive was to be aqcuired by Sammy. If you haven’t heard of Sammy, it’s because you don’t live in Japan and don’t play pachinko. Sega’s continued existence paradoxically relied on a hardware business (ableit a different kind of game hardware) in order to keep its software ambitions alive. But how many out of the last seven Sonic games released in the last seven years have you truly enjoyed?

Nintendo is not in this position financially. There’s only one company (in Japan, anyway) that has the cash to acquire Nintendo, and since they make cars they’re probably not interested.

Nintendo has so much money, in fact, it makes far more sense for them to never leave the hardware market.

1) Nintendo is sitting on several Mt. Fujis of sweet cash

Like we said earlier, Nintendo has been on top more often than not.

Nintendo has been so on top since the release of the Wii home console in 2005 that they are now sitting on mountains of yen. That mountain is so high, that the dedicated video game company surpassed $10 trillion yen ($85 billion) in assets for the first time in 2007. Despite that Sony is a larger, more diverse business with higher revenues, Nintendo keeps a vastly higher percentage of the money coming in. By Q3 2007, Nintendo’s value rose so much that they were second only to Toyota as Japan’s most valuable company — surpassing even the likes of Mitsubishi, and, yes, Sony.

Nintendo has been so on top since the release of the Wii home console in 2005 that they are now sitting on mountains of yen. That mountain is so high, that the dedicated video game company surpassed $10 trillion yen ($85 billion) in assets for the first time in 2007. Despite that Sony is a larger, more diverse business with higher revenues, Nintendo keeps a vastly higher percentage of the money coming in. By Q3 2007, Nintendo’s value rose so much that they were second only to Toyota as Japan’s most valuable company — surpassing even the likes of Mitsubishi, and, yes, Sony.

As we covered in the previous point, Nintendo is the only hardware maker left standing from its original competitors in the 1980s. Were they to leave now, Sony and Microsoft (and, if you believe it, Apple) would be the only ones left. Microsoft’s entry into the video game market cost the company nearly $5 billion dollars to make its Xbox brand known, and to remain successful with its successor console. In 2007, Nintendo had enough cash on hand to perform that feat 17 times over, and they had three more years of meteoric growth before they finally posted a loss.

As we covered in the previous point, Nintendo is the only hardware maker left standing from its original competitors in the 1980s. Were they to leave now, Sony and Microsoft (and, if you believe it, Apple) would be the only ones left. Microsoft’s entry into the video game market cost the company nearly $5 billion dollars to make its Xbox brand known, and to remain successful with its successor console. In 2007, Nintendo had enough cash on hand to perform that feat 17 times over, and they had three more years of meteoric growth before they finally posted a loss.

Nintendo can literally afford for its next several consoles to not be smash hits. They slashed the price of the 3DS by one third before it was even out for a year, subsequently breaking the sales records of the DS, and still made money in the process.

If anyone should get out of the hardware business, it’s Sony. They’ve had a third-rate home console and a third-rate handheld for most of the last decade, and the PS Vita isn’t looking to fare much better. Sony had better get out while the getting’s good, and leave Microsoft and Nintendo to duke it out.

My money’s on Nintendo.

Now excuse me while I go play some Arkham City… on my Xbox 360.

PS3

PS3

Famicom Dojo

Famicom Dojo KEEP PLAYING

KEEP PLAYING KEEP PLAYING: Rewind

KEEP PLAYING: Rewind Powet Toys

Powet Toys Powetcast

Powetcast Hitchhiker's Guide POWETcast

Hitchhiker's Guide POWETcast